Will I Ever Be Good Enough?

Have you wondered where your internalized message of "I'm not good enough," comes from? Do you feel you give life your best, work hard, try hard, but still can't give yourself credit? Are you constantly beating yourself up and thinking that somehow you should be more, do more, be better, and you don't measure up in your own mind?

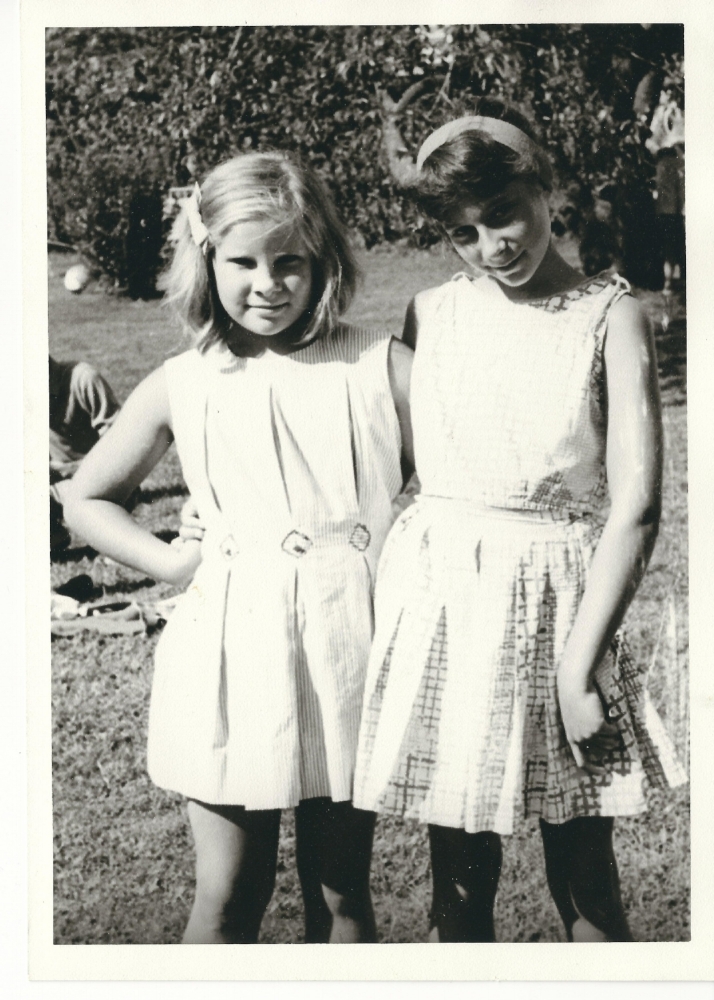

Aunt Deedy & Mom, East Hampton, 1958

Have you wondered where your internalized message of "I'm not good enough," comes from? Do you feel you give life your best, work hard, try hard, but still can't give yourself credit? Are you constantly beating yourself up and thinking that somehow you should be more, do more, be better, and you don't measure up in your own mind?

But how does the message "I'm not good enough" get internalized? Where does this come from? To start with, I want you to think about small children and how impressionable they are, how they are soaking up life and trying to learn and understand the world around them. And, the most important thing to them is gaining love and affection from their caregivers. They do not yet have a worldly or experienced understanding of human behavior or why people behave in certain ways. Their main goal is to be loved, and this is of course, what every child deserves.

So, given that the child's goal is to be loved and cared for, the child begins to try to "fix" the adult problems so they can achieve their goal. They don't do this consciously, of course, but many start this at a very early age. "If only I was a better kid, this would not be happening." "If I did better in school, my parents wouldn't fight." "If I listen to my parents' problems, maybe they will be less stressed." "If I do more chores or housework, maybe Mommy won't be so sad."

Children are like sponges and take in their environment on emotional levels as well as physical and intellectual levels. They learn very early that if Mommy and Daddy are happy then they themselves will be happier too and get more of the love they need. "When Mommy is happy, she will play with me and spend time with me." "When Daddy is not mad, he will be nicer to all of us." Kids want peace, love and harmony in their lives and need it to thrive emotionally. So, if it is not there, guess what they do? Try to fix it by trying to be a better and better kid, or they may also try the opposite and act out to get their parents to focus on them. But they are learning and internalizing that no matter what they do, they cannot fix their parent's problems. They are kids, and of course this is not their problem to fix, but they don't know that yet. So, they keep trying.

Many times parents in dysfunctional families will blame their children or project onto their children the bad feelings the parent is feeling at the moment. Narcissists do this all the time. They are internally self-loathing, but project this onto their children rather than embrace and resolve their own feelings. It's always someone else's fault. A child knows no different. Of course, they take this on too. "It must be me." "It must be my fault if my parent is mean to me, or can't love me." "I must be unlovable." So the child ends up carrying the emotional baggage of the family and takes on the burden. "If only I could do more, be better."

If this sounds like pieces of your childhood, hopefully you begin to realize the message was wrong. It was not your fault. It was a distorted reality that you had to buy into to survive in a dysfunctional environment. Understanding that is the first step towards healing and unwinding the negative message of "I am not good enough." You can also begin to take ownership of your own life, play with those voices in your head, and realize that you can change yourself as an adult and be who you want to be.

The Body Keeps the Score : Recovering from Trauma

When a person experiences traumatic events, the aftermath can be extremely debilitating. Trauma not only affects the mind, but can have lifelong effects on the body. For survivors, their bodies feel deeply unsafe, so the enemy that was once living outside is now living within. So they need to befriend their bodies, safely go inside and experience themselves. There is too much emphasis on the capacity of the cognitive rational brain to conquer our irrational survival brain. You can't rely on reason, you need rely on mastery of your body, safety of your body, finding peace in your body. You need to find some way where your body once again feels like "I am in control of myself."

Wedding Day. By Della Chen.

When a person experiences traumatic events, the aftermath can be extremely debilitating. Trauma not only affects the mind, but can have lifelong effects on the body. Trauma is an experience that overwhelms your capacity to cope. People feel helpless, overwhelmed, scared, horrified.

For trauma survivors, their bodies feel deeply unsafe, so the enemy that was once living outside is now living within. They need to befriend their bodies, they need to calm their bodies down. Yoga is more effective than medication; medication can be nice to dampen some of the symptoms. But in the end, people need to own their bodies, they need to own their physical experiences. And, in order to overcome your trauma, it needs to be safe to go inside and to experience yourself.

There is too much emphasis on the capacity of the cognitive rational brain to conquer our irrational survival brain. Neuroscience has really helped us understand that you can't talk yourself out of being in love, or being angry, or hating particular people because these are not rational processes. Reason has only very limited capacities to override these more primitive survival issues. And so, you need to not rely on reason, you need rely on mastery of your body, safety of your body, finding peace in your body. You need to find some way where your body once again feels like "I am in control of myself."

- From Bessel Van der Kolk, author of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

The following is an excerpt from the book:

Mindfulness

At the core of recovery is self-awareness. The most important phrases in trauma therapy are “Notice that” and “What happens next?” Traumatized people live with seemingly unbearable sensations: They feel heartbroken and suffer from intolerable sensations in the pit of their stomach or tightness in their chest. Yet avoiding feeling these sensations in our bodies increases our vulnerability to being overwhelmed by them. Body awareness puts us in touch with our inner world, the landscape of our organism. Simply noticing our annoyance, nervousness, or anxiety immediately helps us shift our perspective and opens up new options other than our automatic, habitual reactions. Mindfulness puts us in touch with the transitory nature of our feelings and perceptions. When we pay focused attention to our bodily sensations, we can recognize the ebb and flow of our emotions and, with that, increase our control over them.

Traumatized people are often afraid of feeling. It is not so much the perpetrators (who, hopefully, are no longer around to hurt them) but their own physical sensations that now are the enemy. Apprehension about being hijacked by uncomfortable sensations keeps the body frozen and the mind shut. Even though the trauma is a thing of the past, the emotional brain keeps generating sensations that make the sufferer feel scared and helpless. It’s not surprising that so many trauma survivors are compulsive eaters and drinkers, shun making love, and avoid many social activities: Their sensory world is largely off limits.

In order to change you need to open yourself to your inner experience. The first step is to allow your mind to focus on your sensations and notice how, in contrast to the timeless, ever-present experience of trauma, physical sensations are transient and respond to slight shifts in body position, changes in breathing, and shifts in thinking. Once you pay attention to your physical sensations, the next step is to label them, as in “When I feel anxious, I feel a crushing sensation in my chest.” And you can begin to notice how these sensations constantly shift and change.

Practicing mindfulness calms down the sympathetic nervous system, so that you are less likely to be thrown into fight‑or‑flight. Learning to observe and tolerate your physical reactions is a prerequisite for safely revisiting the past. If you cannot tolerate what you are feeling right now, opening up the past will only compound the misery and retraumatize you further.

Once we are fully aware that the commotions in our bodies are in a constant state of flux we can tolerate whatever discomfort comes up. One moment your chest tightens, but after you take a deep breath and exhale, that feeling softens and you may observe something else, perhaps a tension in your shoulder. Now you can start exploring what happens when you take a deeper breath and notice how your rib cage expands. Once you feel calmer and more curious, you can go back to that sensation in your shoulder. You should not be surprised if a memory spontaneously arises in which that shoulder was somehow involved.

A further step is to observe the interplay between your thoughts and your physical sensations. How are particular thoughts registered in your body? (Do thoughts like “My father loves me” or “my girlfriend dumped me” produce different sensations?) Becoming aware of how your body organizes particular emotions or memories opens up the possibility of releasing sensations and impulses that you may have learned to block in order to survive.

Relationships

Study after study shows that having a good support network constitutes the single most powerful protection against becoming traumatized. Safety and terror are incompatible. When we are terrified, nothing calms us down like the reassuring voice or the firm embrace of someone we trust. Frightened adults respond to the same comforts as terrified children: gentle holding and rocking and the assurance that somebody bigger and stronger is taking care of things, so you can safely go to sleep. In order to recover, mind, body, and brain need to be convinced that it is safe to let go. That happens only when you feel safe at a visceral level and allow yourself to connect that sense of safety with memories of past helplessness.

After an acute trauma, like an assault, accident, or natural disaster, survivors require the presence of familiar people, faces, and voices; physical contact; food; shelter and a safe place; and time to sleep. It is critical to communicate with loved ones close and far and to reunite as soon as possible with family and friends in a place that feels safe. Our attachment bonds are our greatest protection against threat. For example, children who are separated from their parents after a traumatic event are likely to suffer serious negative long- term effects. Studies conducted during World War II in England showed that children who lived in London during the Blitz and were sent away to the countryside for protection against German bombing raids fared much worse than children who remained with their parents and endured nights in bomb shelters and frightening images of destroyed buildings and dead people.

Traumatized human beings recover in the context of relationships: with families, loved ones, AA meetings, veterans’ organizations, religious communities, or professional therapists. The role of those relationships is to provide physical and emotional safety, including safety from feeling shamed, admonished, or judged, and to bolster the courage to tolerate, face, and process the reality of what has happened.

As we have seen, much of the wiring of our brain circuits is devoted to being in tune with others. Recovery from trauma involves (re)connecting with our fellow human beings. This is why trauma that has occurred within relationships is generally more difficult to treat than trauma resulting from traffic accidents or natural disasters. In our society the most common traumas in women and children occur at the hands of their parents or intimate partners. Child abuse, molestation, and domestic violence all are inflicted by people who are supposed to love you. That knocks out the most important protection against being traumatized: being sheltered by the people you love.

If the people whom you naturally turn to for care and protection terrify or reject you, you learn to shut down and to ignore what you feel. When your caregivers turn on you, you have to find alternative ways to deal with feeling scared, angry, or frustrated. Managing your terror all by yourself gives rise to another set of problems: dissociation, despair, addictions, a chronic sense of panic, and relationships that are marked by alienation, disconnection, and explosions.

Patients with these histories rarely make the connection between what happened to them long ago and how they currently feel and behave. Everything just seems unmanageable. Relief does not come until they are able to acknowledge what has happened and recognize the invisible demons they’re struggling with.

While human contact and attunement are the wellspring of physiological self-regulation, the promise of closeness often evokes fear of getting hurt, betrayed, and abandoned. Shame plays an important role in this: “You will find out how rotten and disgusting I am and dump me as soon as you really get to know me.” Unresolved trauma can take a terrible toll on relationships. If your heart is still broken because you were assaulted by someone you loved, you are likely to be preoccupied with not getting hurt again and fear opening your heart to someone new. In fact, you may unwittingly try to hurt them before they have a chance to hurt you.

This poses a real challenge for recovery. Once you recognize that post-traumatic reactions started off as efforts to save your life, you may gather the courage to face your inner music (or cacophony), but you will need help to do so. You have to find someone you can trust enough to accompany you, someone who can safely hold your feelings and help you listen to the painful messages from your emotional brain. You need a guide who is not afraid of your terror and who can contain your darkest rage, someone who can safeguard the wholeness of you while you explore the fragmented experiences that you had to keep secret from yourself for so long. Most traumatized individuals need an anchor and a great deal of coaching to do this work.

I Don't Know What I Feel?

- I'm numb a lot of the time.

- It's like I have no emotions.

- Something is missing in me.

- I feel empty inside.

- What's it all for? What's the point?

- Why am I here? What am I supposed to be doing?

- Does anything really matter?

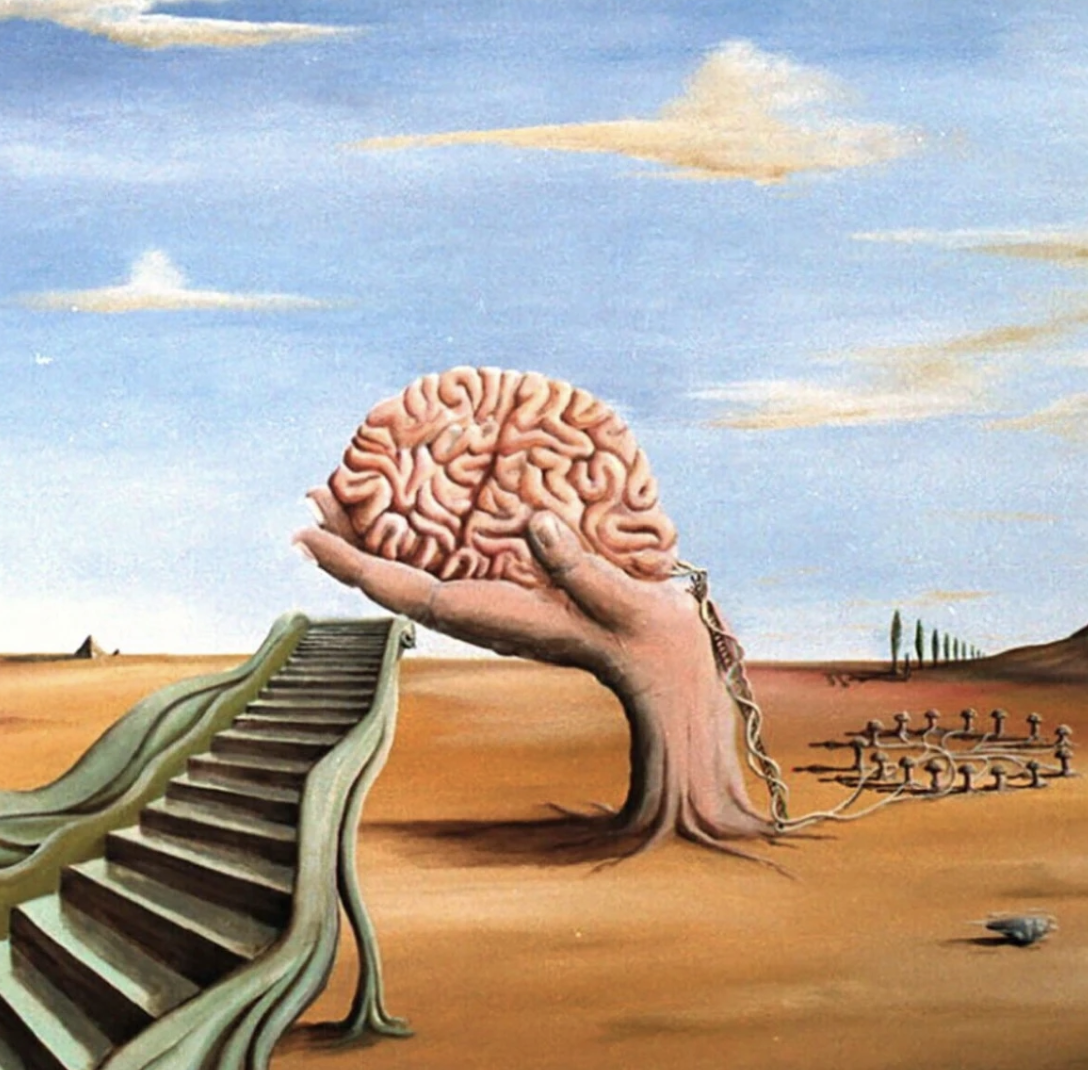

Hope of a Condemned Man by Joan Miro

I don't know what I feel or what I want.

I'm numb a lot of the time.

It's like I have no emotions.

I can't really remember my childhood.

I feel empty inside.

I'm depressed but I don't know why.

Why am I here? What am I supposed to be doing?

Shouldn't I feel happier and more fulfilled?

In Running on Empty: Overcoming Your Childhood Emotional Neglect, Dr. Jonice Webb identifies the widespread, but little understood, phenomenon of Childhood Emotional Neglect.

It's not about what happened to you as a child, it's about what failed to happen for you as a child. It's an extremely subtle, almost invisible factor and it disrupts one's life in untold ways. Mostly the feeling is: Empty.

It's a feeling of something absent or missing inside of you, of being different, set apart, alone, lacking, numb. This is a feeling that can drive people to do a myriad of unhealthy things, like overeat, overdrink, over-shop, or use drugs. This is a feeling which gradually, quietly erodes a person’s joy, energy and confidence. It flies under the radar, and carries with it a tremendous power to degrade your quality of life.

It can be very confusing because often people who feel these ways grew up in relatively healthy, happy homes. So why would I feel this way?? There must be something wrong with me. This is the first book to give this experience a name and delve into the profound and often perplexing ways it influences our adult satisfaction and happiness.

You can find much more information on Dr. Jonice's website, Emotionalneglect.com.

Choosing a Therapist

Even more important than the specifics of the therapist's training, is the relationship between the two of you, which actually begins before the first session. Do you feel basically comfortable with this therapist? Does he or she seem to feel comfortable in his or her own skin and with you as a fellow human being? The critical question is this: Do you feel that your therapist is curious to find out who you are and what you need?

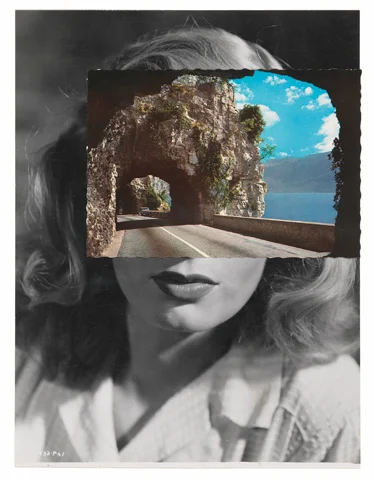

Mask series by John Stezaker

There is no one "treatment of choice" for psychotherapy. No therapist can possibly be familiar with every effective treatment, and he or she must be open to your exploring options other than the ones he or she offers. He or she must also be open to learning from you.

While it's inappropriate and unethical for therapists to tell you the details of their personal struggles, it is perfectly reasonable to ask what particular forms of therapy they have been trained in, where they learned their skills, and whether they've personally benefited from the therapy they propose for you.

Even more important than the specifics of the therapist's training, is the relationship between the two of you. Do you feel basically comfortable with this therapist? Does he or she seem to feel comfortable in his or her own skin and with you as a fellow human being? Feeling safe is a necessary condition for you to confront your fears and anxieties. In my experience, clients' symptoms improve more quickly if both parties develop positive feelings and respect for one other. I also don't think that you can grow and change unless you feel that you have some impact on the person who is treating you.

The relationship begins before the first session. It starts with the time you spend on his or her website. Does it strike a chord with you or is it generic mumbo jumbo? Do you feel a sense of hope, believe this person can help you? Does he or she get back to you quickly when you call? Is this person's style more friendly and casual or professional and clinical? What do you prefer? Is there a willingness to be flexible with schedule or fees? How does your gut feel? What kind of energy does this person have? Do you think you might be able to spend hours sitting with him or her, expressing distressing thoughts and allowing yourself to be vulnerable?

The critical question is this: Do you feel that your therapist is curious to find out who you are and what you need? Are you just a list of symptoms on some questionnaire, or does your therapist take the time to find out why you do what you do and think what you think. Therapy is a collaborative process - a mutual exploration of your self. The therapist can provide illumination, new perspectives, practical resources, but ultimately you are the expert of your own life.

See also: How to Find the Right Therapist in The New York Times

Why Do You Want to Be in a Relationship?

If you are a person who wants to be in a relationship, have you thought about why? Actually, there are two very different reasons for wanting a relationship. The first is about what you want to get, and the second is about what you want to learn and share.

Korakia Pensione, Photo Della Chen

If you are a person who wants to be in a relationship, have you thought about why? Actually, there are two very different reasons for wanting a relationship. The first is about what you want to get, and the second is about what you want to learn and share.

Wanting a Relationship in Order to Get

If you ask people why they want a relationship, many will say things like:

I don’t want to be alone and lonely anymore.

I want to have children.

I want someone to love me and make me feel special and worthy.

I want to feel safe and secure.

What they might not say outright is that they want a relationship to:

Complete them. They hope that their partner will give them what they are not giving to themselves and what they might not have received as children.

Fill the empty place within them.

Make them feel taken care of emotionally, financially and/or sexually.

You might be thinking, “Right! Aren’t these the reasons everyone wants a relationship? Why be in a relationship if not to be loved, cherished, made to feel special, safe and secure? What’s the point of a relationship if not to fill me, take away my loneliness and make me feel okay about myself?”

There really is another reason for wanting to be in a relationship.

Wanting a Relationship in Order to Heal, Learn and Share Love

The other reason for being in a relationship stems from the fact that relationships are the most fertile ground for learning about what is unhealed in us, and for having an arena to heal. Most of us have baggage from childhood that we carry into our primary relationship — such as fears of rejection and fears of engulfment. These fears generally get played out with a partner, which offers us an incredible opportunity to learn about and heal them. Relationship can be the Ph.D. of personal growth!

Learning about your fears of intimacy, as well as about control issues that may surface with a primary partner, can lead to much personal growth — enhancing your ability to love. The more you learn to take responsibility for your own feelings — learning to love yourself, cherish yourself, make yourself feel special and valued — the more you may want a relationship in order to share your love rather than to get love. Contrary to what many believe, it’s not the getting of love that takes away loneliness, but the sharing of love.

The most profound and beautiful experience in life is the sharing of love. But we can’t share our love unless we are filled with love. When we learn to fill ourselves - with presence, with love from nature, spirit, the energy of the universe or whatever that is for each person — then we come to our partner with inner fullness rather than with inner emptiness. Rather than needing a partner to complete us, we desire to share our completeness with our partner.

When two people come together to get love rather than to learn, heal and share love, there is a strong possibility that their relationship won’t last. With both partners trying to get loved and filled by the other, and neither one having learned to love and fill themselves, each will ultimately be disappointed.

When two people come together because they want to learn together, grow together, heal together, share their time and companionship, and share their love and passion, they have a good chance of creating a lasting, loving relationship.

When these people are asked why they want a relationship, they say:

I want to learn and grow with someone who also wants to learn and grow.

I have a lot of love to give and I want to share it with a partner, who also has a lot of love to give. Possibly, we might want to have children with whom to also share our love.

I want to share time, companionship, lovemaking, laughter and play with someone with whom I feel deeply connected.

If you tune inside and honestly ask yourself why you want a relationship, and you find yourself on the first list rather than on the second, do not despair. You can learn how to love yourself and fill yourself with love so that you have plenty of love to share with a partner.

It’s important to realize that we attract people at our common level of health — which is the level of taking personal responsibility for our happiness and wellbeing — or at our common level of self-abandonment — which includes making someone else responsible for our feelings. Given this reality, you have a far better chance of creating a healthy and loving relationship with a partner when you have a healthy and loving relationship with yourself.